What’s With the Mean Sushi Chefs?

Some days I think the most influential Japanese chef in America might actually have been John Belushi.

If you’ve seen Belushi’s “Samurai Delicatessen” skit, originally performed on Saturday Night Live in 1976, you’ll remember him channeling a touchy Japanese chef, perpetually on the verge of violence, who screamed out loud while slicing ingredients with a sword.

Belushi’s character was a riot, but would you really want him making your lunch? Apparently, for many sushi lovers in America, the answer is “yes.”

Consider this inquiry I received from a reader named Peter the other day:

Does etiquette permit a customer to request sushi without any wasabi? I’ve always been afraid to ask. … There are those famous sushi chefs who kick you out of the restaurant.

Here we have a patron with a simple request–no different, in fact, from a customer at a deli who asks that his sandwich be “very lean on the corned beef,” as the customer does in Belushi’s “Samurai Delicatessen.”

Yet poor Peter is genuinely terrified that the chef will banish him for his insolence, if not disembowel him with a fish knife.

It seems to me that no dining experience should involve this much fear. Unless you’re deliberately after a plate of poisonous blowfish. But as Peter’s comment reveals, many sushi chefs in America have built reputations by inspiring just such dread.

Chief among these is probably Kazunori Nozawa in Los Angeles, whose habit of ejecting customers for minor infractions of etiquette earned him the nickname “the Sushi Nazi”–a formulation borrowed from a popular episode of Seinfeld that featured a dictatorial soup vendor called “the Soup Nazi.”

Every profession has its share of nitpickers and curmudgeons. So why have Nozawa and his ilk acquired such fame? Last fall, the Wall Street Journal even published a report about them called “The Sushi Bullies.” The article claimed that such behavior is the norm in Japan.

But the article also quoted a Japanese chef and instructor named Toshi Sugiura who said quite the opposite–that traditionally, sushi chefs are trained to be polite and friendly, like neighborhood bartenders. So which is true? Is the caricature of the crazy samurai chef based in reality or not?

Sugiura is someone I happen to know well, having spent several months watching him work behind his sushi bar. He has a forceful personality, but he’s more monk than samurai–he wins you over with his warmth. He inspires his American customers to follow proper etiquette, and eat authentic sushi, without threatening anyone with eviction. In fact, his customers are his pals, and the atmosphere at his sushi bar can be delightful and even boisterous.

My own experience of Japanese chefs in Japan, acquired while residing there for several years and eating sushi with Japanese friends at their favorite sushi bars, was that they were more like friendly neighborhood bartenders than surly samurai.

There’s a well-known short story in Japan called “Sushi,” written in 1939 by Kanoko Okamoto, that gives a sense of what a typical old-school sushi bar ought to be like. The chef knows his customers by name and remembers what each one likes to eat and in what order. The atmosphere is relaxed, sometimes even silly.

Why, then, do we assume that Japanese chefs should be tyrants, and that we should put up with their reign of terror, and even reward it? Maybe it’s because we believe we’re getting something authentic. We conjure up a vision of the stern Japanese warrior  and feel obliged to become his supplicants. If that’s the case, I can think of a word that describes this impulse well: masochism.

and feel obliged to become his supplicants. If that’s the case, I can think of a word that describes this impulse well: masochism.

I’d rather enjoy good food along with good company and be treated with respect and perhaps even a dose of charm. Chefs like Sugiura are proof it’s possible for a sushi master to educate Americans into the finer points of their tradition without making us feel like juvenile delinquents.

I’d even argue that sushi chefs ignore at their peril the fact that the relationship between restaurateurs and customers should be a two-way street.

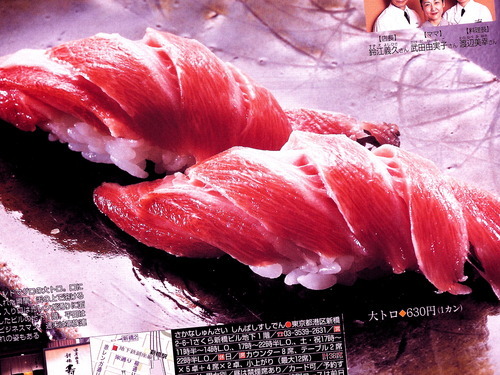

Take bluefin tuna. Most sushi chefs are still blindly serving it, but consumers are waking up to the fact that it’s becoming an endangered fish. I myself won’t eat bluefin anymore. But does etiquette permit a customer to request sushi without it?

Take bluefin tuna. Most sushi chefs are still blindly serving it, but consumers are waking up to the fact that it’s becoming an endangered fish. I myself won’t eat bluefin anymore. But does etiquette permit a customer to request sushi without it?

It certainly ought to, and even the most stubborn of chefs had better listen. Because if they don’t, sooner or later they’ll lose business to the hip new sushi joint next door that just started serving a menu of sustainable seafood.

As for requesting sushi with less wasabi, wouldn’t it be nice if our friend Peter could feel comfortable enough to ask without fearing for his life? Because then he might learn from his friendly neighborhood chef that sushi with less wasabi is actually the more authentic choice.

“Sushi with too much wasabi is just bad sushi,” the chef would say, smiling. “Here, try this piece, I’ve made it with just the right amount of wasabi–only a tiny bit.”

And if Peter still felt it was too much for him, the chef could act like that chef in the Japanese short story, and say, “Okay, from now on, I’ll remember to put almost no wasabi at all in your sushi.”

And probably, Peter would keep going back to that sushi bar for the rest of his life.

John Belushi was a comedic genius. For my money, the samurai chef shouldn’t be something to fear. It should remain, as Belushi intended, something to laugh at.

Screen shot at top: Saturday Night Live on Hulu.com.

This post was first published on The Atlantic.