The Global Catch

It’s hard to believe there was a time when most Americans would rather eat a tuna sandwich than sushi. Or watch Ultraman instead of Iron Man. As a kid in the seventies I probably started watching Ultraman around the same time I started eating canned fish between slices of bread. Both were a low-budget half-mechanized sort of sustenance. Japanese sci-fi; the triumph of technology over nature.

It’s hard to believe there was a time when most Americans would rather eat a tuna sandwich than sushi. Or watch Ultraman instead of Iron Man. As a kid in the seventies I probably started watching Ultraman around the same time I started eating canned fish between slices of bread. Both were a low-budget half-mechanized sort of sustenance. Japanese sci-fi; the triumph of technology over nature.

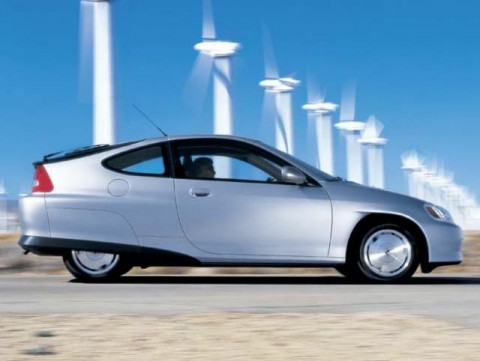

Decades later American food had begun its gourmet revolution and a sandwich shop near my office featured its signature item “The Nicoise,” which got me eating tuna between bread again. Japanese sci-fi dreams had progressed a ways, too. Around the same time, the first Japanese hybrid car hit the market. I asked myself “What would Ultraman drive?” and bought one.

As much as I would enjoy being like Bruce Wayne, I haven’t slipped on an Ultraman suit to pilot my spacey silver hybrid car around Gotham at night. But if I did, and I encountered a giant tuna fish terrorizing the financial district, I would first subdue it with my Marine Spacium Beam (that’s the マリンスペシウム光線 for those of you keeping track). And then I would call Japan Air Lines and ask for the cargo division. For the gourmet food revolution has entered a whole new phase, and so has the Japanese sci-fi technology that enables it.

As much as I would enjoy being like Bruce Wayne, I haven’t slipped on an Ultraman suit to pilot my spacey silver hybrid car around Gotham at night. But if I did, and I encountered a giant tuna fish terrorizing the financial district, I would first subdue it with my Marine Spacium Beam (that’s the マリンスペシウム光線 for those of you keeping track). And then I would call Japan Air Lines and ask for the cargo division. For the gourmet food revolution has entered a whole new phase, and so has the Japanese sci-fi technology that enables it.

In a matter of hours JAL Cargo would put my freshly slaughtered giant tuna fish on ice in a high-tech container and fly it to Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market for sushi, and I would hang up the Ultraman suit, trade in the Honda hybrid for a Lamborghini, and retire as a billionaire.

In a matter of hours JAL Cargo would put my freshly slaughtered giant tuna fish on ice in a high-tech container and fly it to Tokyo’s Tsukiji fish market for sushi, and I would hang up the Ultraman suit, trade in the Honda hybrid for a Lamborghini, and retire as a billionaire.

Eerily like watching Ultraman as a kid was how I felt watching promotional footage from the 1970s that’s been newly released from the archives of JAL Cargo and included in a new documentary film called Sushi: The Global Catch. (I’ll be hosting a couple of screenings of the film in New York City; more on that below.) The vintage reel shows lab-coated Japanese engineers developing the original sci-fi-ish cargo container kit that allowed JAL Cargo to begin transporting fresh giant bluefin tuna between continents by air, a tricky science akin to cryonics. It’s easy to forget what an absurd proposition that was at the  time, when all we knew and cared about was canned chicken of the sea between slices of mushy bread.

time, when all we knew and cared about was canned chicken of the sea between slices of mushy bread.

Meanwhile, one of the most gripping parts of the documentary for me was one of its most understated moments—a quiet interview with Akira Okazaki, a JAL Cargo executive who is something of a legend in Japan but little-known in the West. As my fellow sushi journalist Sasha Issenberg has reported, in the 1970s Okazaki and his colleagues were trying to solve a very specific problem: after dropping off 747s full of Sony Walkmans in America, JAL Cargo was flying its planes home to Japan empty. What did North America produce at the time that the Japanese could be convinced to buy? Not much. It is Okazaki who is credited with the idea of filling JAL’s planes with bluefin tuna.

What Okazaki and his colleagues did changed everything. Until the mid-20th century, tuna had been a garbage fish seldom used for sushi.  After JAL Cargo’s technical and logistical innovations, bluefin became such a priceless global commodity that now many of its populations are in danger of being wiped out. It’s a stunning reminder of how a cultural habit that we imbue with the dignity of tradition, and that can be as intimate as what we put inside our bodies for dinner, can turn out to have been literally engineered just a few short years ago by a corporate marketing team.

After JAL Cargo’s technical and logistical innovations, bluefin became such a priceless global commodity that now many of its populations are in danger of being wiped out. It’s a stunning reminder of how a cultural habit that we imbue with the dignity of tradition, and that can be as intimate as what we put inside our bodies for dinner, can turn out to have been literally engineered just a few short years ago by a corporate marketing team.

The most touching parts of the documentary for me were the scenes from a remote fishing village called Oma on the northernmost tip of Japan’s main island, where a white-haired curmudgeon named Hirofumi Hambata, chairman of the local fishermen’s co-op, states his profound concern about the global overfishing of bluefin tuna, and explains why Oma’s small-town bluefin are the most sought-after by sushi chefs. Having worked as a small-boat commercial fisherman in a remote village myself, I was heartened to hear one of Tokyo’s best chefs describe how Oma fishermen catch bluefin from a small boat with a single hook & line. It’s described in the video clip below.

And not included in this clip, but in the film, is a moment when Hambata makes a point that particularly resonated with me, because it’s something I mention at every one of the historical sushi dinners I host: in sushi, there are so many other delicious fish to eat besides tuna that aren’t endangered. To hear a Japanese tuna fisherman who serves the highest end of the sushi market say this is profound.

Sushi: The Global Catch is opening in New York City this weekend and the distributor has hired me to host a couple of post-screening Q&A sessions about what’s depicted in the film. More details here of when I’ll be on site at Quad Cinema. Hope to see some of you wearing your Ultraman suits.

(Tuna sushi photo above: The Delicious Life.)